Go Back

Go BackShare

Early Childhood Education in India – Landscape, Challenges, and The Road Ahead

By The EDge Editorial Team

Aug 25, 2022

In our conversation with Venita Kaul, Professor Emerita (Education), Ambedkar University, Delhi, we deliberate on her vast research experience in ECE, the current state of early-learning outcomes in India, and best practices that we can learn from. She reflects on the role of various key stakeholders, the need for convergence between both ministries, and suggests concrete actions across many levels to improve ECE in the country.

Venita Kaul is Professor Emerita (Education), Ambedkar University, Delhi, from where she retired in 2016 as Director of School of Education Studies and Founder Director of Center for Early Childhood Education and Development (CECED). Prior to this, Prof. Kaul was a Senior Education Specialist in The World Bank after having served as Professor and Head of Department of Preschool and Elementary Education at NCERT for over twenty years.

Professor Kaul and colleagues with ASER and UNICEF conducted The India Early Childhood Education Impact (IECEI) study, which followed a cohort of 14,000 4 year olds for five years i.e. upto the age of 8 years from 2011-2016 in three Indian states. The study aimed at estimating the immediate impact of early childhood education (ECE) experience on school readiness levels of children and the sustained impact (of preschool experience) on children’s educational and behavioural outcomes during primary grades.

CSF interviewed her to get an understanding of the ECE landscape in India today and her recommendations for ensuring quality ECE for all children in the country.

CSF: What is the status of early childhood education outcomes in India, especially for children from lower income communities?

Venita: From an outcomes point of view, we are seeing that India is doing well in terms of participation, enrollment, and attendance. In our own longitudinal research that we conducted with ASER, we found that nearly 80% of the children were attending some pre-school. Although, when we look at other data, it drops down to about 30-40%. One of the major challenges in early childhood education in India is the lack of a rigorous data system. The data points we have are scattered, asymmetric, incomplete, and sporadically put together.

Having said that, I do feel that there is demand for ECE. Most parents support the idea of their children going to school. While they may not send their 3-year-olds, they want to enroll their children somewhere by the age of four. Where we need greater awareness is “what kind of institution parents need to send their children to”. Anganwadi Centers, which deliver integrated child development services (ICDS), have the reputation of a khichdi centre (food/nutrition program) amongst parents, and therefore, it is not seen as a place where learning can happen. As a result of this, children are either enrolled in private pre-schools or directly in grade 1 in government schools, which are more “studying” focused, and here children miss out on the experience of quality ECE. Pre-school participation in Anganwadis as per MWCD data is showing a decline.

No matter where the children are going, developmental outcomes have been a matter of concern, in terms of both school readiness levels and other cognitive domains due to developmentally inappropriate pedagogy and learning priorities. The situation could be much worse after two years of the pandemic.

CSF: How can we leverage the momentum from the NEP to improve ECE provisions in India?

Venita: I think that the National Education Policy (NEP) is a tremendous opportunity for ECE. It has given a remarkable spurt to it by laying down its importance, especially by creating emphasis on the scientific nature of foundational learning, and how ECE and primary schooling are more on a continuum than separate structures.

The challenge is that we don’t look at ECE as a sector. This leads to our current ECE provisioning channels (Balvatikas, Anganwadis, and private pre-schools) working in silos and their efforts contradict each other. Private pre-schools are more formal and teaching-based, while the government messaging is all about play-based education. Since private channels are more prestigious, they tend to become the pace and trend setters, leading to parents choosing them as opposed to government channels. ECE (reform) should be for the entire sector, both government and private, and be looked at from a sector lens as opposed to a programmatic lens.

Subsequently, we need to set and achieve minimum quality standards across the sector which are non-negotiable, and define clear outcomes for school readiness levels along the continuum. The way government and primary channels provide for them can differ, but the learning environment and priorities must be consistent. This includes:

- Curriculum: Clearly define foundational competencies/skills for early childhood years along the continuum from 3 to 8 years. Our current understanding of foundational learning is misunderstood and restricted to the alphabet and numbers which leads to downward extension of primary schooling, which is developmentally inappropriate and counterproductive for school readiness. Ensuring an engaging program with a balanced, play-based pedagogy is important.

- Prioritize developmental outcomes: Define foundational skills to be achieved based on scientific priorities on what children need to learn at a specific age, focused holistically on cognitive, physical, and socio-emotional development of children.

CSF: How can we increase convergence between the Ministry of Education (MoE) and the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) with respect to early childhood education in India?

Venita: Convergence between both departments/ministries is important. If you go by the experience of the Sarva Shiksha Abhiyaan or the District Primary Education Program, they used to have an executive committee for primary and elementary education to guide and monitor the program. My experience is that this was more effective in states where the committee was chaired by the Chief Secretary, instead of the respective Education or Women and Child Development Secretaries as the hierarchy helped interdepartmental collaboration! The convergence was better. In Thailand, the Deputy Prime Minister heads the committee for early childhood care and education (ECCE) and each department has an annual plan of action for ECCE supported with a budget. Since the Chair’s position is above all the other heads of departments, it is smoother to bring about convergence and also accountability due to an allocated departmental budget.

CSF: We know that a big constraint today is that the learning time is simply inadequate across all channels of ECE provision. What would be your suggestions to improve/optimize learning time in ECE classrooms?

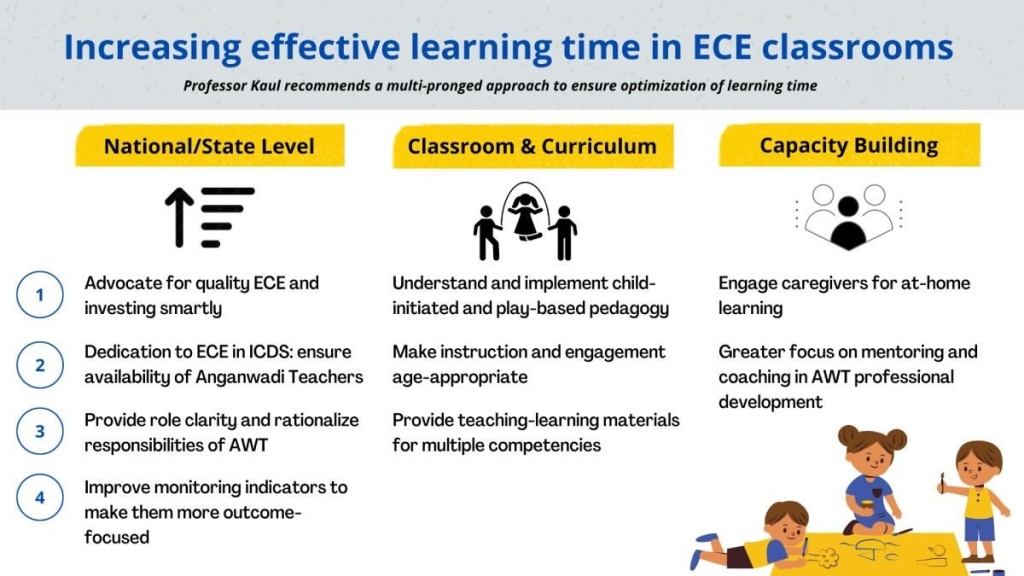

Venita: This can be achieved in multiple ways.

At a National/State level,

- Advocacy: We need to advocate for ECE and ensure government funds are invested in sustainable solutions. Investing in the foundation of learning (ECE) is more important than only in the walls you create!

- Dedication to ECE component of ICDS: A government order can/should be placed that ensures availability and time dedication of Anganwadi teachers (AWTs) for ECE. They need to be available for early childhood education in classrooms every day during the dedicated hours, among their many other roles and responsibilities, which also need to be rationalized.

- Role clarity and rationalization: There are many responsibilities of the AWT – vaccination, health, nutrition, etc. Very often there is an overlap/duplication of responsibilities with the Asha worker. We need to make sure there are clearer task definitions between AWTs and Asha workers, which will relieve AWT to do their thing. For instance, there are only one or two registers (out of said 13) that have to be filled on a daily basis. They need to be told that they need not be burdened to fill all of them everyday. They need to be facilitated so that they can use their time optimally.

- Improving monitoring indicators: Currently the ICDS measures the number of 3 to 6 year olds enrolled and the number of days pre-school education is held. That is not helpful since we all know what is monitored gets done. One of the challenges for people in ECE is to have well-defined monitoring indicators, for both children and program quality, which are measurable and easy for stakeholders, to help give it importance and the structure needed.

On a classroom and curriculum level:

- Better understanding of pedagogy: ECE pedagogy is more child-led than teacher-led. One does not need to constantly engage in direct and lecture-based teaching. As a matter of fact that can be counter productive for children’s learning and development at this stage. There is scope for children to learn a lot on their own.

- Age-appropriate engagement: It is important to meet children where they are and engage with them in an age-appropriate manner. One way to ensure this is to have the Anganwadi teachers form small groups of children (according to age or levels ) and rotate between these groups to facilitate free and structured play alternatively and thus be able to provide direct guidance even in mixed age group settings.

- Teaching Learning Materials: We need to provide innovative and age-appropriate learning materials that speak to different competencies and at different levels of development. These could improve sensory and pre-numeracy/literacy skills of children as well as support socioemotional learning and development. Activity corners for free play should be an essential component of every preschool programmer all the way up to grade 2.

For capacity building of key stakeholders:

- Parental engagement: Parents often do not see value in playing as a mode of learning. They need to be made aware of what comprises good quality early childhood education or foundational stage education. Once they are aware, they can even be guided on what they could do at home to promote children’s learning. This has no budgetary implication.

- Professional Development of Anganwadi Teachers: Mentoring and coaching is more important than training. We need to create a set of mentors in the system who are able to handhold Anganwadi teachers and helpers. They need not necessarily be school staff but need to be oriented on early childhood education.

What are the current gaps in research in ECE and what evidence do we need to generate? How will we know 3 to 5 years from now if we are making progress or moving in the right direction?

Venita: Theoretically, we know that ECE has the potential to narrow or even eliminate the equity gap. There is not enough research in India on what type of curriculum can help achieve that. We need more data on what is the minimum program that is cost-effective and will bring in the quality to bridge the equity gap. Secondly, we also need more action research on curriculum that is devised based on NEP, with continuity till class 2 and is implemented at an adequate scale through a rigorous program that can help us understand the impact through quality indicators that are important to measure. Finally, we do not have data on privileged children. We need data across segments so that we can understand to what extent and what kind of curriculum is important and what role does the environment of learning play in achievement of learning outcomes.

In the next 3-4 years, we will know we’re going in the right direction if we see State level ECE initiatives being planned and implemented and have all concerned departments focused on ECCE, showing elements of collaboration/convergence with adequate understanding of ECCE. We can already see some progress in this area. We can see that the concept of continuum is accepted and we are seeing an overall greater acceptance of foundational learning. This will also need lots of media efforts and advocacy across the sector.

Keywords

Authored by

The EDge Editorial Team

CSF

Share this on