Go Back

Go BackShare

Learning Poverty: A New Kind of Poverty Facing India’s Children

By Debleena Majumdar

Dec 27, 2019

Imagine this. A young child studying in a primary school in a remote location in India, getting access to good quality education and learning all important skills that can change their world and open up opportunities to fulfil their dreams.

Imagine this. A young child studying in a primary school in a remote location in India, getting access to good quality education and learning all important skills that can change their world and open up opportunities to fulfil their dreams.

However, in reality, many of these children are attending schools, but completely lacking in even basic skills such as reading simple text, that form the foundation of all learning.

In a new and urgent way to look at this, the World Bank has introduced the concept of learning poverty. Their results show that 53% of children in low- and middle-income countries are not able to read or understand simple text by age 10. This comes nearly 5 years after the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). What’s more worrying is that despite multiple interventions across countries, at the current rate of improvement, 43% of kids will still be ‘learning-poor’ by 2030.

So, what is learning poverty really, and how can it be addressed effectively?

Defining Learning Poverty

While it is easy to talk about foundational skills and the snowball effect that the lack of these gateway skills can have on lifelong learning and employability, it is hard to measure them accurately.

Basic literacy and numeracy are what most studies break down foundational skills to. However, even as foundational learning encompasses so much more, one skill is more fundamental than the others – READING. Reading proficiency helps children learn better in all other subjects. And, it can be measured effectively.

This is why, learning poverty is defined as being unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10. It is expected that by this age, children should be able to “independently and fluently read simple, short narrative and expository texts,” “locate explicitly-stated information” and “interpret and give some explanations about the key ideas in these texts.” If they can do this, it allows them to ‘read to learn’ in later years.

The Learning Poverty index

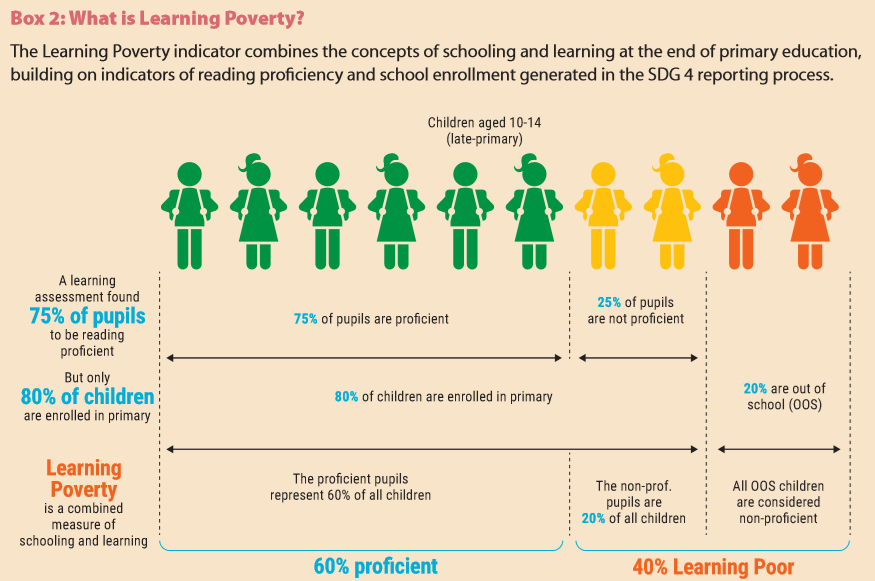

Is it possible for an early reading indicator to help spot low learning levels and solve for it? That is what the learning poverty index aims to do, by combining shortfalls in school access and learning in one simple measure. Quite simply, it looks at reading proficiency rates from standardized learning assessments and discounts it by the share of out-of-school (OOS) primary school children to ensure that figures are comparable and cover both the quantity and quality aspects of schooling.

The World Bank analysis shows that the global learning crisis is still severe – one out of every two children in the developing world is not learning to read by late primary school age. This rate is even higher in low-income countries, at close to 80% and above in sub-Saharan Africa.

Tackling the Crisis

There is a grim warning underlying the report – Even if countries reduce their learning poverty at the fastest rates we have seen so far in this century, the goal of ending it and achieving universal basic literacy and numeracy will not be attained by 2030.

So, the new Learning Target – cut learning poverty by at least half by 2030.

Although still an ambitious goal, the World Bank proposes four things that countries need to focus on to help their children learn to read:

- Ensuring clear and shared goals, means and measures for literacy across political and technical domains, with reading assessments and early literacy programs aligned with national goals: For example, after Peru was ranked last in PISA 2012, the government mobilized public support for a variety of reforms, including increasing investment and improving teacher capacity. Across the school education system, a clear target was set, that every student should be able to fluently read 40 words per minute in class 2 and 60 words per minute in class 3. These efforts eventually resulted in an improvement in the country’s 2015 PISA score.

- Effective teaching for literacy: Teachers in low-income countries often lack the skills they need to provide effective instruction for reading. To bridge this gap, teachers need to be supported with learning materials and teacher guides that have a step-wise plan, as well as a teacher professional development plan that strongly emphasizes practicing specific classroom skills. For example, the successful EGRA (Early Grade Reading Assessment) Plus program in Liberia combined structured lessons for teachers with observation and feedback from literacy coaches.

- Timely access to better age- and skill-appropriate texts: The availability of quality, age-appropriate books or reading material is critical to achieve fluency. In Mongolia, better access to books led to a 0.21 standard deviation improvement in student outcomes. Vietnam is another strong example, where a 2013 Young Lives report found that 97% of students owned a Vietnamese textbook – by 2015, Vietnam has reached the OECD student average in learning levels.

- Instruction in the local language: With English being a foreign language for many students, research shows that students who are taught in their home language in the early years have higher comprehension. It also provides the foundation to more easily learn a second language and study more complex topics later on. This needs to be kept in mind while designing policies for the language of instruction in schools.

In addition, any interventions to promote literacy need to be backed by the entire education system through system-wide reform, a strong political commitment as well as the use of technological solutions to bolster impact. It is also important to provide measurement and action-oriented research that can support these efforts. This will help countries to know where they stand in terms of early literacy, and design effective policies accordingly.

The bottom line is that current approaches are not working well enough to achieve change at the required pace, and need a booster dose. And while the learning poverty index is a new way to measure the gap in learning, it also suggests an integrated way to address the crisis.

Where does India stand?

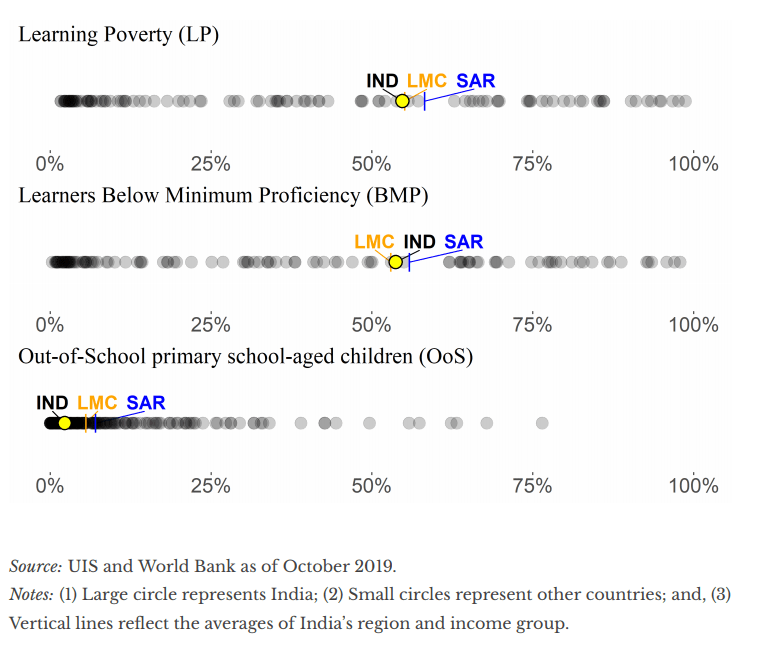

In India, nearly 55% of children are ‘learning-poor’ today, in spite of high levels of enrolment. However, this is based on data from the country’s National Large-Scale Assessment (NLSA) – India has not participated in the World Bank’s Learning and Assessment Platform (LeAP) diagnostics, nor in the cross-national Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) since 2009.

However, there has been increasing attention on the importance of foundational learning in India recently, and the country will also be participating in PISA 2021. The newly released School Education Quality Index (SEQI) by NITI Aayog aims to shift the focus to learning outcomes. Meanwhile, the new National Education Policy (NEP) drafted by the government – the first update in almost three decades – explicitly calls out the importance of the early years and states that all other initiatives to improve education would be “largely irrelevant” if the fundamental skills of reading, writing and arithmetic are not first achieved. This has been backed by several government initiatives as well as efforts by not-for-profit organizations to tackle the problem at multiple levels. Together, these interventions and policy changes can drive a systemic change that can help India bring down its learning poverty levels.

As the report shows, India – which has the maximum number of primary school-going children – still has a long way to go to ensure foundational learning for all. With increasing technological changes and job obsolescence, as per UNESCO, 750 million adults worldwide will have issues reading and writing. While the learning poverty approach may be still evolving and there are gaps in data coverage with fragmented assessment systems, the World Bank report is the latest to highlight the urgency of the issue and make a crying call for action. And we need to respond. With thought. And with action.

The World Bank report, Ending Learning Poverty: What Will It Take? is available at https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/32553.

Keywords

Authored by

Debleena Majumdar

CSF

Share this on