Go Back

Go BackShare

Can School Readiness Programs Work? Learnings from Karnataka and Gujarat

By Snigdha Serikari

Mar 29, 2019

Can School Readiness Programs Work? Learnings from Karnataka and Gujarat

Extensive research in child development and neuroscience indicates that the first five years of life play a crucial role in a child’s lifelong development. Very specifically, before children enter formal schooling in class 1, it is essential for them to be equipped with the appropriate cognitive, pre-literacy and pre-numeracy skills that are required to succeed in the school environment, which differs substantially from the home environment. These skills are collectively referred to as school readiness, and include the ability to pay attention in the classroom, follow instructions, interact with peers, identify some shapes and colours, recognize patterns, correlate alphabets to their sounds, count numbers, and even learn how to hold a pencil.

Unfortunately, most children in India do not have these basic gateway skills as they begin school. Pre-schooling in India has still not been universalized – the largest coverage of 3- to 6- year-olds is by the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) program of the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD), which caters to approximately 3.7 crore children through 13.4 lakh anganwadis (child care centres). However, early childhood education is just one of six (and arguably the least prioritized) functions of an anganwadi worker. There is a burgeoning private sector in this space, but is unregulated and provides a set of largely inappropriate inputs.

In the long term, it is obvious that India needs to universalize quality pre-schooling through a combination of different mechanisms. But, given the fiscal and policy constraints, such a solution would likely be many years in the making. An immediate-term option to equip children with key school readiness skills as they enter class 1 could be an accelerated School Readiness Program (SRP).

An accelerated SRP would essentially be a 40-day program undertaken in class 1 at the beginning of the academic year. It would aim to build the competencies necessary for a child to adjust in a school environment and keep pace with the primary school curriculum.

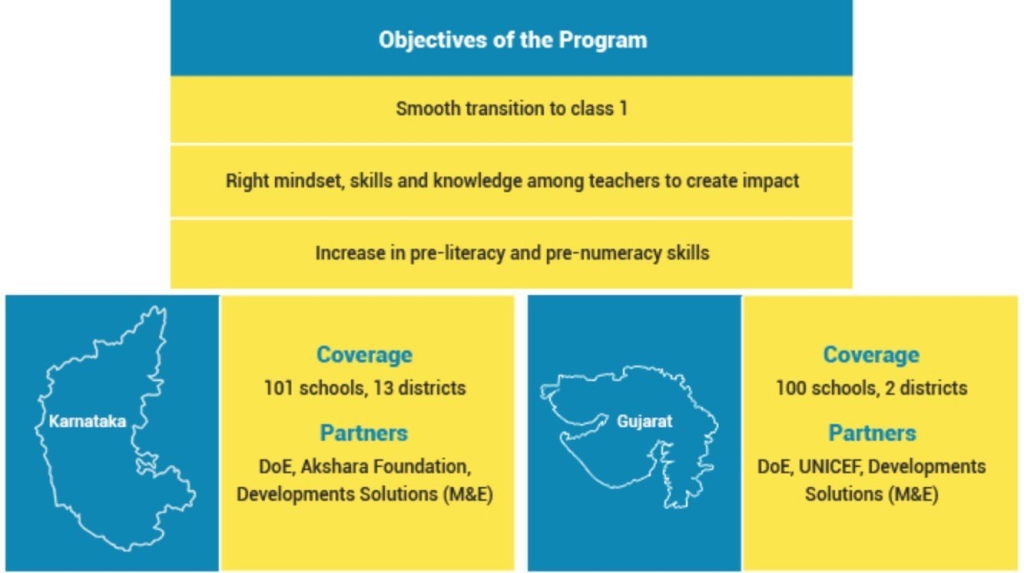

Based on preliminary positive evidence from similar programs in Ethiopia and Cambodia, Central Square Foundation set out to pilot an accelerated SRP in a couple of states in India, covering over 5,000 children in class 1. We aligned on the program objectives with two state governments, Karnataka and Gujarat, found strong technical partners to develop curricula and train the teachers (Akshara Foundation in Karnataka and UNICEF in Gujarat), and signed on an independent M&E agency to do a basic pre- and post-program testing.

As expected in the first year of a program, there were a number of challenges in the roll-out that provided important learnings for future interventions. An important insight was the need for consistent and clear messaging to teachers, headmasters and administrators to help them better understand the need for the program and their expected roles. In the absence of that, there was lack of integration of the SRP program with the respective class 1 curricula. There were also variabilities in classroom management, instructional hours, and consequently duration of the program across classrooms. However, peer learning groups for teachers on WhatsApp and frequent monitoring of the classroom delivery by state officials ensured smooth execution of the program in most schools. Teachers gained a lot from the program, and the feedback on the training program was very positive. Most teachers felt that engagement levels in the class had considerably increased and that a lot of kids felt confident in expressing themselves by the end of the program. A teacher in Hassan, Karnataka said she found that students were curious to learn, could recall all the lessons and thoroughly enjoyed the activities conducted by her as part of the program.

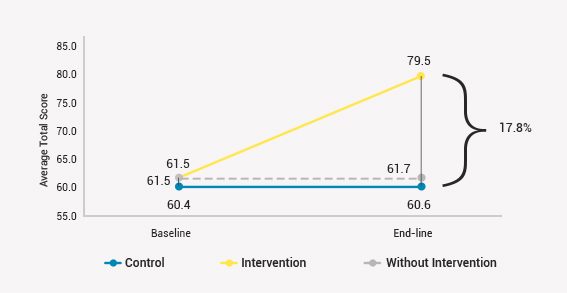

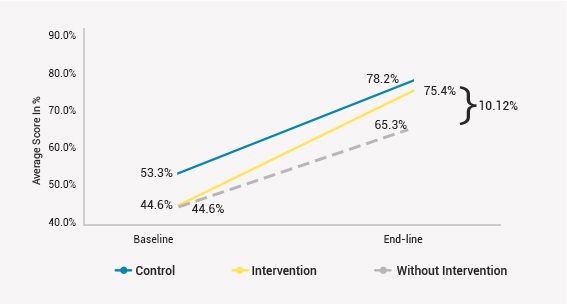

The scores from the pre- and post-program testing were also encouraging. Children who participated in the School Readiness Program had significantly higher scores in both early numeracy and literacy components when compared to the control group who did not participate in the program. In Karnataka, for instance, there was ~18% positive change in the cognitive development scores.

Positive change in cognitive development scores

The initial pilots have given some meaningful insights into how a quality intervention can be piloted using the existing state machinery and helped understand the potential challenges of scaling up such a program. There is also scope to work further to identify the ideal composition of the curriculum for an accelerated SRP, the choice of tools, sampling techniques, and evaluation techniques. For instance, the baseline scores in motor skills of the students were relatively much higher (85%), with a minimal positive gain after the program. This indicates the need to focus more on developing the cognitive and pre-literacy skills of students rather than their physical development.

While these discussions around the program need to continue, the preliminary data and the feedback from stakeholders has been promising. It is clear than an accelerated School Readiness Program has the potential to be a low-cost solution that can bridge school readiness gaps in children at the start of class 1. CSF aims to incorporate these learnings into a larger pilot next year, with the objective of generating more rigorous evidence on the efficacy of this approach.

Keywords

Authored by

Snigdha Serikari

Program Manager, CSF

Share this on