Go Back

Go BackShare

Universal Preschool: Is This a Dream or Can It Be a Reality for India?

By Rukmini Banerji, Chief Executive Officer, Pratham Education Foundation

May 27, 2025

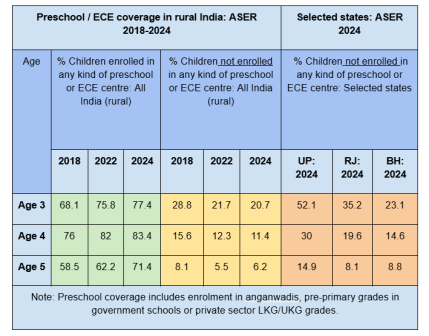

In this article, Rukmini Banerji (CEO, Pratham Education Foundation) with CSF, reflects on India’s progress toward achieving universal preschool education, noting that by 2024, over 75% of three-year-olds and more than 83% of four-year-olds in rural areas were enrolled in some form of preschool. It underscores the need for sustained efforts to achieve universal access to early childhood education by 2030, in line with the vision of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020.

The years 2020 to 2022 will be remembered for two reasons. One, due to the pandemic, schools remained shut across the country for almost two years. Second, it was in this period that the new National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 was launched and preparations for translating the policy into practice began in full earnest. A major change brought in by NEP 2020 was the integration of and focus on the age three to six as part of the education system. This shift opened immense and important new opportunities for the country in terms of building strong foundations for children’s learning. NEP 2020 states that we must have universal provisioning of early childhood education (ECE/ECCE) by 2030. The policy envisions this happening in a phased manner via different pathways. Children can be enrolled in Anganwadi Centres (run by the Ministry of Women and Child Development), in pre-primary grades in government primary schools, or be enrolled in LKG/UKG in private schools or stand-alone early childhood education centres. Another key recommendation of NEP 2020 is to “recruit workers/teachers specially trained in the curriculum and pedagogy of ECCE” to enable the setting up of a ‘Preparatory Grade’ for every child before the age of five (NEP 2020, 1.4)

How far has India come in terms of meeting these NEP 2020 goals?

One possible source for answering this question is data from the series of ASER reports (Annual Status of Education Report). Based on a representative sample of children from the nation-wide household survey of rural districts across India, ASER is able to provide estimates of enrolment over time for the age group three to six.

Three clear trends emerge from analysing available ASER data in India:

1. Substantial progress towards universal preschool coverage

ASER defines preschool coverage to include enrolment in Anganwadi centres, pre-primary grades in government schools, LKG/UKG in private schools and any standalone preschool or ECE centres. Based on this definition of preschool enrolment, we can see that by 2024, over three-quarters of all three-year-olds and more than 83% of four-year-olds in rural India are enrolled in some form of preschool.

The proportion of children not enrolled in any kind of preschool is also dropping over time and by age.

However, there are a few states where a substantial percentage of three and four-year-old children are not enrolled. In these states, younger children (age three) are less likely to be enrolled than older children (age five). The importance of universal preschool coverage is as much for school-readiness as it is for the overall development and well-being of the child. By being part of the Anganwadi system, children can have immunisation and health coverage and nutritional inputs. Hence, ensuring that from age three onwards, children are enrolled in a preschool centre is an urgent and high-priority task.

2. Variety of provisioning solutions and pathways for five-year-olds

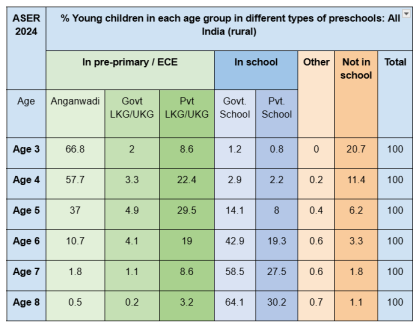

The age five cohort of children is very interesting in India today. Data shows that a majority (71.4%) of five-year-olds are enrolled in pre-primary or early childhood institutions (ASER 2024). As for the rest, 22% are in formal school (usually in Grade 1) and the remainder 6.2% are not enrolled anywhere.

Within the preschool sector, the predominant categories are Anganwadis on the one hand and private preschool grades on the other. An interesting trend of pre-primary grades in the government primary schools is also emerging. (This will be explored further in the following sections).

The picture for five-year-olds however, varies substantially when we look closely at states over time.

2. a. States with high Anganwadi enrolment of five-year-olds

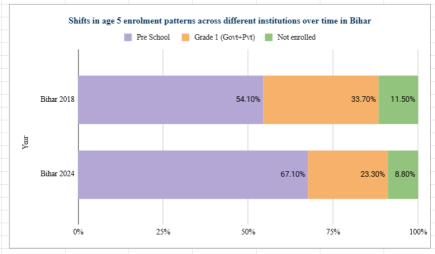

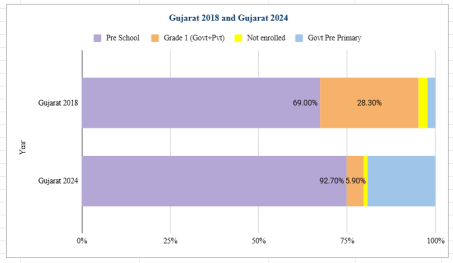

Our first set of illustrative cases are from Bihar and Gujarat – both states where close to half of all children aged five are enrolled in Anganwadis.

In 2024, in rural Bihar, 67.1% of children aged five are in preschool as compared to 54% in 2018. There has been an increase in Anganwadi enrolment of five-year-olds, coinciding with a decline in five-year-olds attending Grade 1 in government schools

The picture in Gujarat is quite different. In 2018, 67% of five-year-olds in Gujarat were in preschool. By 2024, this number increased to almost 93%. This big change has come about as a result of the introduction of pre-primary grades in government schools.

2. b. States with low Anganwadi enrolment of five-year-olds

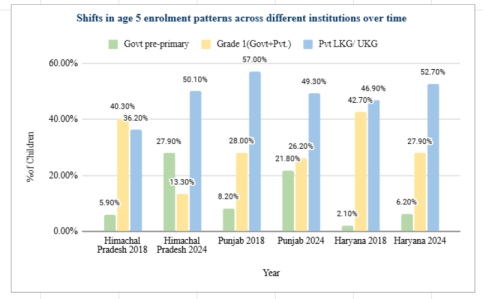

Let us look at some contrasting cases – three northern states – Punjab, Himachal Pradesh and Haryana – where private preschooling is high and Anganwadi enrolment of five-year-olds is very low.

Both Punjab and Himachal Pradesh had started investing in pre-primary grades in government primary schools several years before NEP 2020 was launched. By 2024, close to 28% of five-year-olds in Himachal and approximately 22% in Punjab are attending preparatory grades in government schools. In the period between 2018 and 2024, Punjab has seen a drop (from 57% to 49%) in enrolment in private preschools. In Himachal Pradesh, between 2018 and 2024, there is a drop in five-year-olds entering Grade 1 both in government schools and in private schools. In Haryana, the main shift that is visible is a decrease in five-year-olds in both government and private schools and an increase in enrolment in private preschools.

Broadly, looking at implementation by state governments so far, three major strategies are visible for the current phase (from when schools opened after the pandemic till now):

- Strengthening ECE in Anganwadi: In states where a substantial proportion of five-year-old children are currently enrolled in Anganwadis, a practical step has been to strengthen the early childhood education component in the ICDS system via training and on-site support. This is being done in states like Andhra Pradesh.

- Pre-primary grade in school (with trained teachers): In states where pre-primary grades have been started in government primary schools, existing teachers have been trained for dealing with this age group (like in Himachal Pradesh and Punjab). A special mention should be made for Gujarat. By strictly mandating six as the age criterion for entry into Grade 1 and creating a pre-primary grade (Balvatika), the Gujarat government schools have seen a major shift in the age distribution of cohorts proceeding through the primary grades. Although there are six grades in primary school (one pre-primary and five primary grades), Grade 2 has seen (it was Grade 1 last year) very low enrolments this year. Primary school teachers who deal with the Balvatika grades have been trained on ECE, and schools have been given appropriate materials.

- Reinforcing Vidya Pravesh: Most states have implemented the Vidya Pravesh programme — a school readiness phase in the first three months of Grade 1. More than 75% of the government schools that were visited as part of ASER 2024 reported doing school readiness programmes for Grade 1, both in the current and previous academic year.

3. The proportion of underage children in Grade 1 is decreasing over time

Although many policy documents over the last two decades refer to the age group 6 to 14 years as being of elementary school age, in reality, in pre-COVID years, age composition of Grade 1 population included a significant proportion of children who were less than six years old and sometimes even younger than five. In some states, the official age of entry into Grade 1 sometimes was also under six. Parents with high educational aspirations for their children often feel that more schooling years is better for children and hence are keen to enrol children into school at a young age. In fact, most private schools, even in rural areas, do not admit children directly in Grade 1. Private school children often spend one to two years in lower KG and upper KG before coming to the first year of formal school. Starting Grade 1 too early is not advisable. To be able to deal with grade level curricular expectations, the child must be cognitively ready.

Both for policy and for practice, age of entry into formal schooling i.e. Grade 1 is an important structural issue for the education system. At central and state levels, one of the important aspects of operationalizing key recommendations of NEP 2020 has been to mandate age six as the appropriate age for entry into Grade 1.

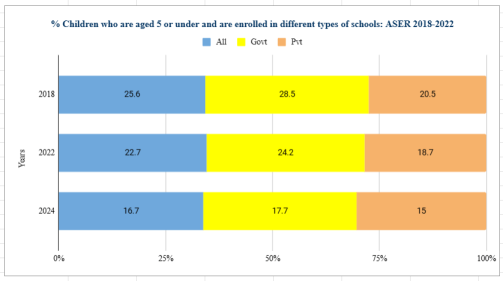

Data on age in Grade 1 over time shows that underage enrolment has dropped sharply between 2022 and 2024, especially in government schools.

By 2024, across rural India, well below one-fifth of children in Grade 1 are underage (i.e. aged five or under). Most states are following the ‘age six’ norm. As this norm gets institutionalised, we should see even lower figures for underage children in the coming years.

As India moves towards quality universal pre-primary provision, several considerations need to be kept in mind:

- Cost considerations and budgetary allocations: A quality preschool/preparatory grade needs a dedicated and trained teacher. Are the current budgetary allocations sufficient to meet this requirement? Cost analyses of appointing new teachers versus strengthening/re-training existing teachers need to be done. Similarly, in states which have high Anganwadi coverage, it will be important to build in training for ECE for coming years. Having a teacher trained in ECE is a NEP 2020 mandate and it should be actioned.

- Collaboration: Collaboration is essential between the two arms of the government that deal with young children (Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Women and Child Development). Their priorities, plans and practices need to be aligned with the vision and goals of NEP 2020 for effective implementation.

- Continuum: A continuum has been envisioned for the foundational stage, not just in terms of provision, but also in terms of curriculum, material, training, instruction, monitoring, support, assessment and smooth transition. High-energy implementation seen in the last few years for first two grades in primary school needs to be connected with the early childhood aspect of the foundational stage in each state.

- Cohort tracking: As India strengthens preschooling, it is essential that each cohort of children enters school and completes first grade with better experiences and outcomes than their previous cohorts.

- Current realities to be used as starting point: Starting with a thorough and grounded understanding of current realities is an essential aspect of any planning process. ASER and UDISE provide some data for this age group, but more comprehensive and continuous data collection efforts are needed to provide relevant information on a timely basis for decision making.

As a country we have made a very promising beginning to help our children acquire foundational learning skills by the time they reach Grade 3. Strengthening and aligning efforts in the preschool years, along with the early grades in school, will truly result in the strongest foundation for children’s learning that the country has seen so far.

Universal preschooling is not a dream for India. We are well on our way to making this a reality for all children in this country.

Keywords

Authored by

Rukmini Banerji, Chief Executive Officer, Pratham Education Foundation

Share this on